For almost a century, expeditions—group trips into wilderness areas where people face physical, mental, and emotional challenges—have been used as an educational tool. Expeditions were initially intended to create a new generation of all-male explorers for the United Kingdom. Today, that rationale may seem as dated and irrelevant as the clothes and equipment used on those early trips.

Why, then, have these trips grown more and more popular over the subsequent decades? Research indicates that expeditions foster personal growth in participants. Pete Allison, associate professor of recreation, park, and tourism management, has spent almost three decades examining how expeditions help people grow into more confident and purpose-driven adults.

“Many times, I have heard the cliché that an expedition changed someone’s life,” said Allison. “I wanted to research whether this was true, and if so, how, and why.”

Components of expeditions

The expeditions that Allison and his colleagues study are immersive trips into rugged natural areas where participants are exposed to challenges related to their capacity, endurance, and decision-making. An expedition might involve backpacking, downriver canoeing, sailing, or ice climbing.

Today, private companies, nonprofits, and educational organizations lead expeditions all across the planet. Expeditions typically involve self-propelled physical journeys like hiking, sailing, or bicycling. They purposely involve some degree of uncertainty, meaning that an important aspect of the trip—like the route or the length of time—is not rigidly defined in advance. Another important aspect of expeditions is immersion in the wilderness where people are cut off from the distractions, comforts, and technological support of modern life. Wilderness settings help introduce an aspect of self-sufficiency to expeditions, like the need for participants to carry personal equipment and food supplies. Expeditions that meet these criteria can lead to significant personal growth among participants.

Author

Aaron

Wagner

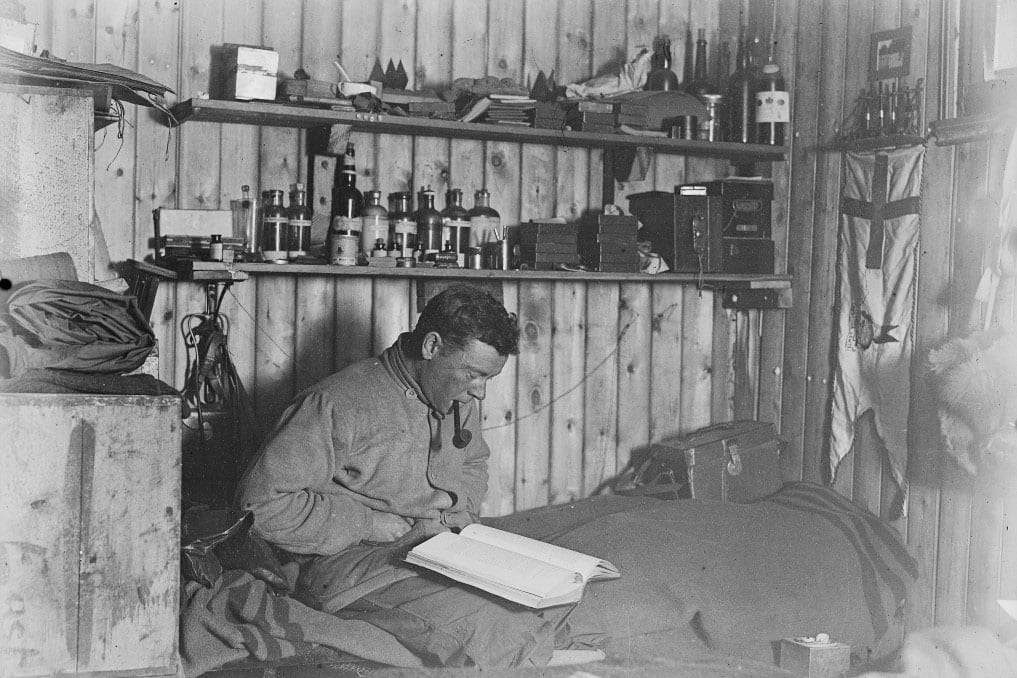

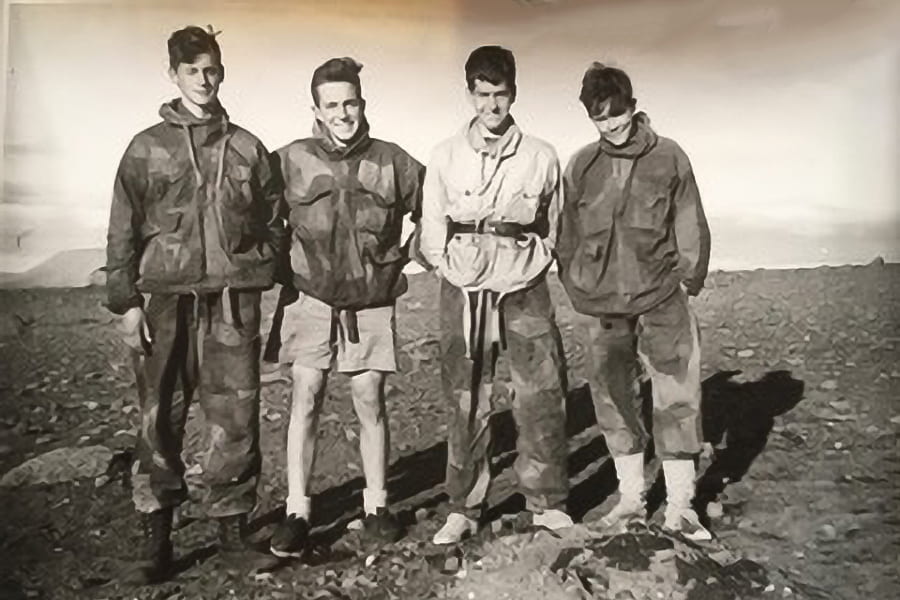

Gear for expeditions—from the luggage, to the backpacks, to the coats—has evolved over the last century. Participation in these trips has grown as their benefits have become better understood.

How expeditions help people grow

“Expeditions build skills that are—by their nature—hard to quantify,” said Allison, “Research has been clear, however, that expeditions improve leadership, teamwork, interpersonal awareness, confidence, and one’s sense of personal purpose. They also increase people’s belief in the value of environmental protection and their desire to contribute to their communities.”

Researchers believe that personal growth stems from an increased ability to manage emotions, thoughts, and behaviors in challenging circumstances. People need these skills to function in an environment when they are making decisions that impact their well-being and the well-being of everyone in their group.

Expeditions should always be led by trained facilitators, according to Allison. Facilitators must allow a group to face challenges without placing themselves in danger. Additionally, facilitators need to allow a group to make its own decisions without allowing the situation to devolve into chaos. When a group makes their own decisions, its members can learn to become more cooperative and confident.

“Early on in an expedition, many groups are concerned about fairness,” said Allison. “For instance, a hiking group might initially decide that everyone has to carry the same amount of weight and consume equal portions of food. Over the first few days, they will see that the group becomes very spread out during a hike because some people carry the weight easily while others struggle.

“Similarly, they may see that some people have more food than they need while others are perpetually hungry. Through experience, the group comes to realize that equality—everyone having the same burdens and opportunities—is not as valuable to the group as equity—differential burdens and opportunities based on people’s individual circumstances. Members of the group may learn to pay attention to and accommodate individual differences, which will help them become better team members and leaders.”

In addition to helping people develop internally, expeditions also increase participants’ understanding of the fragility of the wilderness and their support for environmental protections.

“I think the expedition has raised my awareness of the problems of tourist impact on places that have only been ‘discovered’ recently,” said an expedition participant whom Allison interviewed. “I think that I would be more inclined to support any groups or societies involved with environmental issues now that I have seen what a pristine area is like and the amount of rubbish that was carried out by the few hundred people who had so far visited.”

How to get involved

There are many ways that people can participate in expeditions or support this type of learning for young people. Organizations like Outward Bound (with whom Allison works), National Outdoor Leadership School (NOLS), Road Scholar, The British Exploring Society, The Royal Geographic Society, The Explorers Club and other organizations around the world offer a broad array of expeditions to people of varying ages.

Local scout groups can provide exposure to expedition-like conditions in smaller doses for young people who do not have the time or resources to participate in an expedition.

Early expeditions often included elements of legitimate exploration, as seen in the surveying of new territory (above, left). Modern expeditions may involve activities that are considered leisure sports, like snowboarding (above, center). All these expeditions, however, have shared common characteristics like requiring self reliance in challenging physical settings.

Early expeditions often included elements of legitimate exploration, as seen in the surveying of new territory (top). Modern expeditions may involve activities that are considered leisure sports, like snowboarding (center). All these expeditions, however, have shared common characteristics like requiring self reliance in challenging physical settings.

The power of group dynamics

Research indicates that the unforgiving natural environment creates an interdependence in the group that helps people internalize these lessons and skills. The group dynamic creates a microcosm of society, according to Allison. On an expedition, it is easier for people to see the cause-and-effect relationships of teamwork and physical effort. People who do not cooperate with their teammates will experience frustration and be unable to meet their goals. On the other hand, people who are considerate and kind typically experience kindness from others.

Part of allowing groups to make decisions means permitting them to make mistakes. Once, when Allison was leading an expedition, he allowed a group to hike in a giant circle all day until, that evening, they arrived nearly where they had started after breakfast.

“There are different lessons you can learn from a mistake like that,” Allison explained. “People who selected the route might learn to practice humility rather than assuming they know what they are doing. People who followed without considering where they were going might learn to pay more attention and take personal responsibility for themselves. Perhaps other members of the group noticed that something might have been wrong but were not confident enough to speak up. Those people might learn the importance of making their voices heard. Of course, the discovery of the mistake frustrated everyone in the group, but learning how to remain constructive while dealing with frustration is a very valuable skill, and the group was forced to learn that.”

People grow as individuals through physical and emotional challenges that they are forced to meet. Expeditions foster healthy group dynamics and teamwork because people are reliant on one another to succeed and grow.

“Formative in a positive way”

Despite the research showing that expeditions lead to growth, little research has considered whether these effects remain over the course of someone’s life. To address this gap in the knowledge, Allison and his collaborators interviewed people who participated in a school-based canoeing excursion decades ago.

As high school students in Scotland in the 1970s, participants prepared for a year and then went on a wild-water canoe expedition in France. Forty years later, some participants were interviewed. They attributed many aspects of their personal growth to the expedition, including planning and preparation, confidence, independence, perseverance, and a desire to contribute to their communities.

One of them said, “I’m absolutely clear in my mind that these experiences were formative in a positive way, wanting to take on different challenges. I have done so many different things in my life now. When I came back [from my expedition], I decided to go back to school with a more mature attitude.”

Another participant said, “The resilience you learn being outdoors really added to my education back then and since. These things are massive learnings from the whole time we worked together. That will never leave me.”

Prior research has shown that 90 to 96 percent of participants felt that their experience on expeditions made a difference in their lives. In the end, Allison believes that the personal experience of change is the greatest contribution that an expedition can make in a person’s life.

“This is about helping people write their own narrative,” Allison explained. “We give people the ability to—metaphorically speaking—write their own past, present, and future.”

Health and the environment

Research into environmental effects often focuses on negative exposures, like Amy Snipes research on farm workers and exposure to pesticides, or Larry Kenney’s research on human temperature limits.

The inverse of that, however, is research that focuses on healthy environmental exposures. Allison’s work is a subset of the large body of research that has shown that exposure to nature is healthy.

Experience the wilderness

Embrace your spirit of adventure and join us for “The Wolves and Wilderness of Yellowstone,” a seven-day, wintertime, wildlife expedition in Yellowstone National Park, the best wolf-watching habitat in North America. Peter Newman, Martin Professor of Recreation, Park, and Tourism Management, will guide your exploration as you learn about the animals, environment, hydrothermal activity, and history of the park from January 14 – 20, 2023.

Photo Credits

Header Graphic – Avector and Anton Porkin via Getty images; Full graphic illustration by Dennis Maney

Background Image – Barmaleeva via Getty Images

How to get involved, sidebar – Vadym Ilchenko via Getty Images

Photo gallery photos (9) – Photos courtesy of Pete Allison

Experience the wilderness – Jupiterimages via Getty Images

Author

Aaron Wagner