Center for Childhood Obesity Research

Forming partnerships with Head Start programs to set children on the right path

Note: The child’s name in this story has been changed to protect his identity. This story was originally written in spring 2023.

Struggling to learn

Matthew is a curious, energetic, affectionate four-year-old from Altoona, Pennsylvania who always wants to help the teachers in his Head Start preschool class. He often arrives at his Head Start classroom hungry because there is not enough food to eat at his home.

Both in and out of preschool, Matthew faces many challenges. All children act out, but sometimes Matthew is disruptive to the classroom; ignoring and defying his teachers. His father died, his mother’s boyfriend is in prison, and she has been unable to find consistent work. She says that she often feels overwhelmed because she does not earn a livable wage and lacks social support. Matthew’s home tends to be chaotic. He often arrives at school tired and poorly dressed in dirty clothing; sometimes he even arrives without underwear.

Matthew and his classmates who live in poverty face many experiences and conditions that often make it difficult for them to manage their emotions, increasing the risk for lower academic achievement. Working with the staff in his Head Start class this year, Matthew improved how he responds to his emotions. As June approached, Matthew did not want school to end. His teacher, Christina Pavlock, did not want him to lose the predictability and structure—and food—that school provides.

“He scarfs down food,” Pavlock said. “He knows that he may not be able to fill his belly again for a long time, so when given the opportunity, he eats. Without Head Start this summer, I worry about him having enough to eat.”

Poor eating habits can create lifelong problems for Matthew and the other 3,000,000 children who live in poverty in the United States. Children who grow up in poverty face a host of risks more often than their middle class and wealthy peers. Children in poor households are more likely to experience obesity, heart disease, stroke, and to live shorter lives.

children in the U.S. Live in poverty

children are served by Head Start each year

Partnerships for healthier children

Head Start, a free preschool program for children who live in households at or below the national poverty line, serves 1,000,000 children nationwide each year.

The goal of Head Start is to break the cycle of poverty through early-childhood education. To address the risks faced by children who live in poverty—including unhealthy eating—Head Start employs case workers and forms partnerships with local agencies and universities to address social problems, parenting, diet, and other issues.

In Blair County Pennsylvania, where Matthew lives, Child Advocates of Blair County runs 20 Head Start classrooms across the county. For almost a decade, Child Advocates of Blair County has partnered with the Penn State Center for Childhood Obesity Research (CCOR) in the College of Health and Human Development to bring healthy eating skills to the classrooms, homes, and lives of children living in poverty. Child Advocates of Blair County has opened their classrooms, and in return, the children they serve have participated in evidence-based, early-childhood nutrition and eating-skills programs.

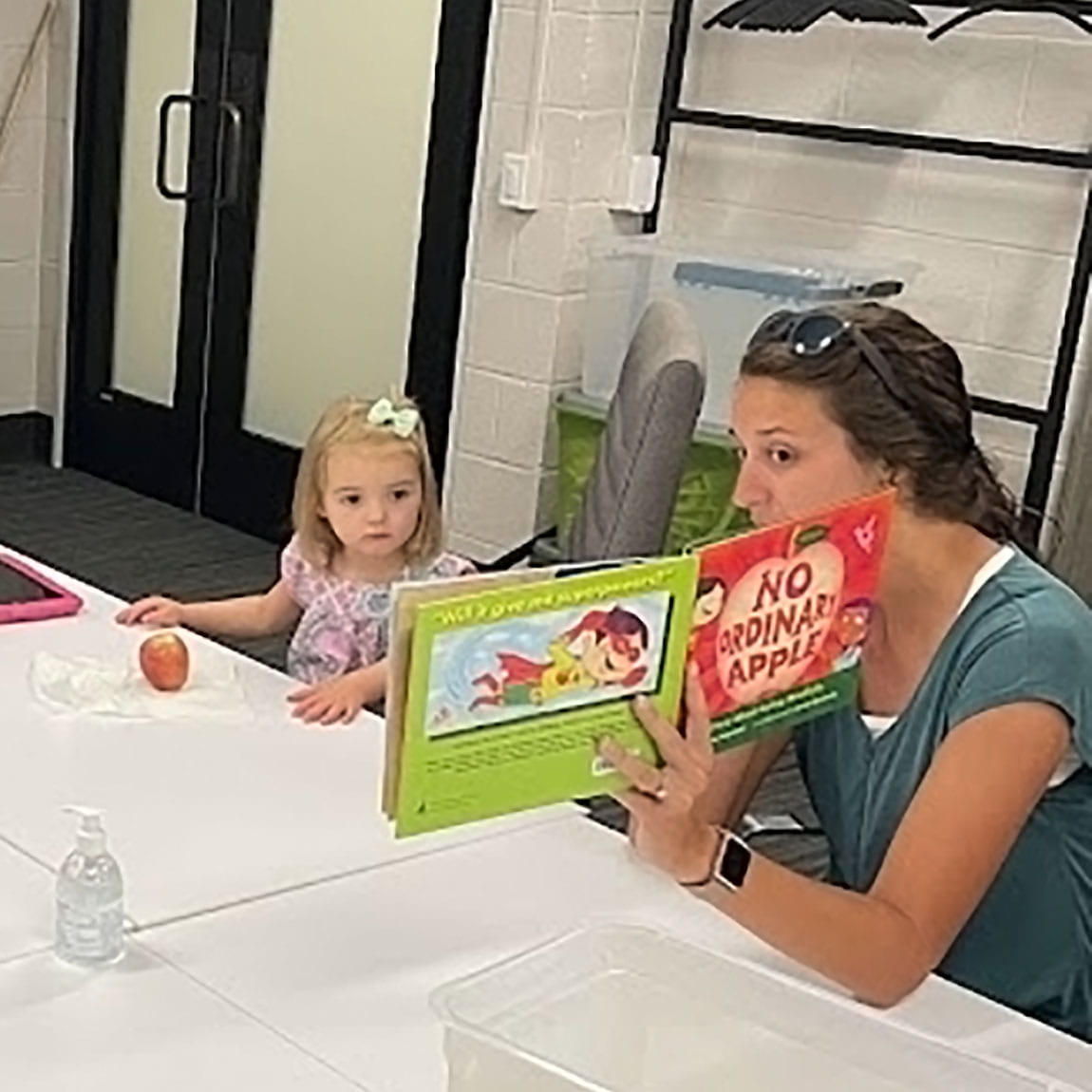

Enganging children and encouraging them to think about food choices.

Preventing childhood obesity

In 1980, one in 20 children in the United States had obesity, but by 2021, that ratio had increased to one in six. By 2016, Pennsylvania was one of only eight states where obesity rates were increasing among two-to-four-year-old children from low-income households.

Childhood obesity is related to problems throughout life including physical health concerns like type 2 diabetes, joint problems, and breathing problems, and mental health concerns like anxiety, low self-esteem, and depression.

This past year, CCOR educators ran a program that teaches healthy, ‘responsive’ feeding strategies to children, their parents, and their teachers in many of Blair County’s Head Start classes. In this caregiver feeding program Responsive feeding includes children and their caregivers working together to pay attention to signals from a child’s body that they have eaten enough food. CCOR educators teach children and their caregivers to ‘listen to what their bellies are telling them.’

1 in 20

children in the U.S. had obesity in 1980

1 in 6

children in the U.S. had obesity in 2021

“The ultimate goal of the program is to improve appetite self-regulation among children,” said Lindsey Hess, research project manager at CCOR. “The main question we are asking is, ‘Can we teach kids to listen to their bodies and stop eating when they are not hungry?’”

In addition to the program teaching responsive feeding skills, CCOR educators work to broaden children’s pallets by introducing them to healthy, unfamiliar foods. In the fall when the school year begins, the educators start with common foods like apples, and by the end of the school year, children are trying foods with which they are less familiar — like asparagus, beets, and cabbage — and sometimes asking for more.

Each time children taste a new food, they are encouraged to use all their senses: noting the food’s smell and appearance, how it feels on the skin and in the mouth, and how it sounds when you bite into it. Then, once they eat, children are encouraged to pay attention to whether their belly feels hungry or sufficiently full. Children say things like, ‘My apple is sour, and I hear it crunch,’ and ‘I hear my belly growling. I am hungry.’

“All of these concepts: engaging their senses, paying attention to the environment, attending to their bodies’ cues, and managing their behavior are valuable beyond mealtimes,” Hess continued. “The same skills help the children manage their emotions and responses properly across other areas of their lives, in the classroom, and at home.”

Lifelong skills for every area of life

The skills that CCOR educators teach are based on research that addresses a child’s overall well-being and health, not just their nutritional needs. For children like Matthew, who have such a complex set of intertwining needs, no problem can be effectively addressed in isolation. The skills that students learn about eating — attending to their senses and reflecting on how they feel — can be developed and transferred to a wide array of important life situations, like conflict management.

“The program that CCOR ran this school year was amazing. It really was,” said Matthew’s teacher, Pavlock. “Not only did they educate children about food and eating and listening to your body, but the lessons also tied in with the social and emotional skills that we teach in the classroom. The CCOR lessons teach important self-regulation skills like taking belly breaths, taking time to think, making choices, and listening to what is going on inside their bodies.

“These skills are really valuable for everyone, and these kids really benefit from this instruction,” she continued.

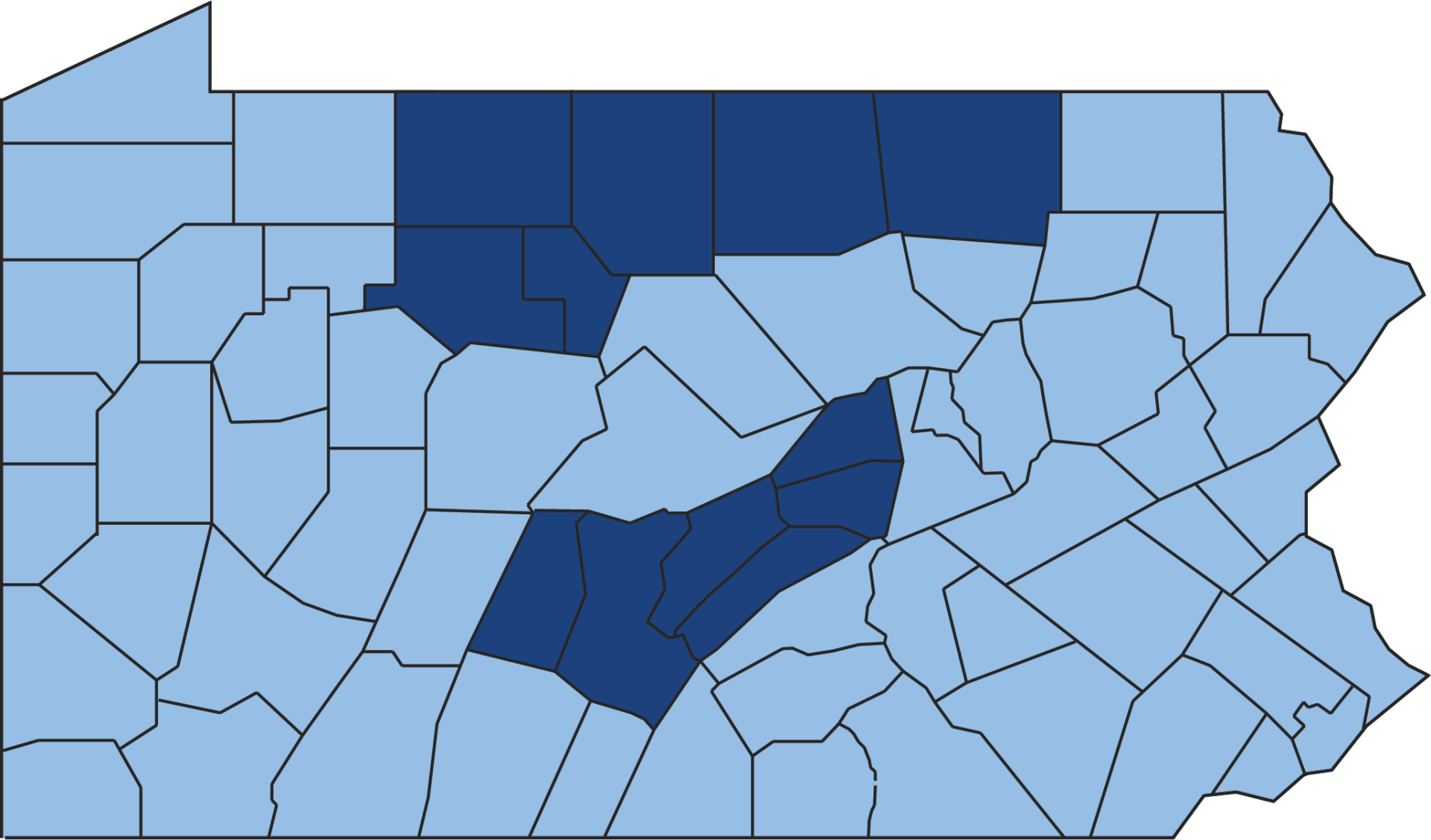

Serving Pennsylvania

CCOR works with Head Start programs in 12 Pennsylvania counties to serve over 1600 children each year.

Krystal Rhodes, Child Development and Education Manager for Blair County Head Start, has worked for Child Advocates of Blair County as both a teacher and supervisor for years. Rhodes said that while the lessons from CCOR have changed over time, all the skills and terminology used in the lessons remain in the minds of children, teachers, and families.

“When talking with Head Start kids and their families — and even with the staff’s own families — those of us who work at Head Start often hear some of the language of the CCOR lessons,” Rhodes said. “These days, we hear kids saying things like, ‘My belly feels just right’ if they have had enough to eat. But I still hear some teachers refer to ‘go foods and woah foods’ — meaning healthy and unhealthy food choices — and those terms are not in the current curriculum. The kids look forward to the CCOR lessons, and they are really fun. More importantly, the lessons have an impact on the way that the children and staff at Head Start think about food and healthy eating.”

Support for parents: Support from parents

One of the most important changes to the CCOR lessons over time has been the addition of parent and teacher education. Children are taught about healthy, thoughtful, mindful eating, and their caregivers are taught how to feed responsively. This allows everyone who supervises the children’s eating to use the same language and terminology and to be on the same page about what constitutes healthy eating behavior.

Parent instruction is very personalized, according to Hess. “Our coach meets families wherever they are without judgement,” Hess said. “What do the families want to focus on? What do their households look like? What is their specific child like as a person, and how does he or she relate to food? These questions drive the conversations in a way that helps the parents feel seen and heard rather than scolded about nutrition.”

Parents who have been surveyed seem to agree. One parent said, “[The lessons] are really helpful and handy. You never feel like you are being told how to parent, just very helpful tips and ideas that actually work.”

The programs that CCOR runs in Head Start are based on research, and the current programs are always being studied to inform future early childhood nutrition and eating programs. This cycle leads to continuously improving education to help meet children’s needs and improve their health. The teachers and staff at Child Advocates of Blair County, the staff of CCOR, and the children’s parents all recognize that the program is working.

As another parent said, “If I had it my way, I would honestly have [the CCOR program] in every school, near and far.”

Parker the puppet, one of the main instructional aids used by instructors, has a see-through belly so that students can visualize the effects of his eating.

The video shows a portion of an instructional session that preschool students receive.

Photo Credits

3 Images of children: Photos supplied by the Center for Childhood Obesity Research

Pennsylvania Map: Image by Ruslan Maiborodin via Getty Images

Puppet: Image by Penn State, courtesy of CCOR.