Supporting Hearing and Speech Development and Recovery

Supporting speech and language to support individuals

Across the region, Commonwealth, and nation, services for speech and language challenges are often hard to access. Pennsylvania has the third highest number of rural residents of any state in the nation, and the further these residents live from an urban center, the harder it often is for them to access many specialized health and medical services.

The Speech, Language, and Hearing Clinic—which recently relocated to a more spacious and convenient location near Beaver Stadium on Penn State’s University Park campus—serves a broad range of people with communication concerns. The clinic provides screenings and therapy for preschoolers, support for people living with Parkinson’s disease, technological and therapeutic support for children who cannot meet all their communication needs verbally, therapy for people whose voice is losing volume and expressiveness due to aging, and diagnoses and therapy for people living with aphasia due to stroke or other health problems.

The clinic also helps people deal with stuttering, which is how Sandeep Krishnakumar came to use the clinic’s services. When Krishnakumar was completing his engineering master’s degree in Colorado and looking for a Ph.D. program, he prioritized finding a university with a speech clinic that he could access.

Krishnakumar was born in India and raised in Qatar in a community of Indian expatriates. Though he began stuttering in early childhood as his language skills developed, it did not seem very significant to him. The stutter became more pronounced, however, as Krishnakumar grew.

“As I aged, I became more aware of people’s impatience or when they were laughing at me,” Krishnakumar explained. “The stutter became worse, and it became a bigger part of my identity. I would work to conceal my stutter because I did not want to bother anyone or take up any space in the conversation.”

– Sandeep Krishnakumar

The stuttering led Krishnakumar to doubt his capabilities. Would he be able to present his research in public? Would he be able to interview for and acquire a job? Throughout his childhood, his stuttering was treated as a problem to be solved. One of the most important skills that Krishnakumar gained through speech therapy at the Speech, Language, and Hearing Clinic was to work with his stutter rather than to struggle against it.

By focusing on the mental and emotional aspects of living with stuttering, the students and faculty at the clinic helped Krishnakumar become his own advocate in professional and social situations. Krishnakumar had to accept his stutter—and his own value to a conversation—in order to move past stuttering when it occurs.

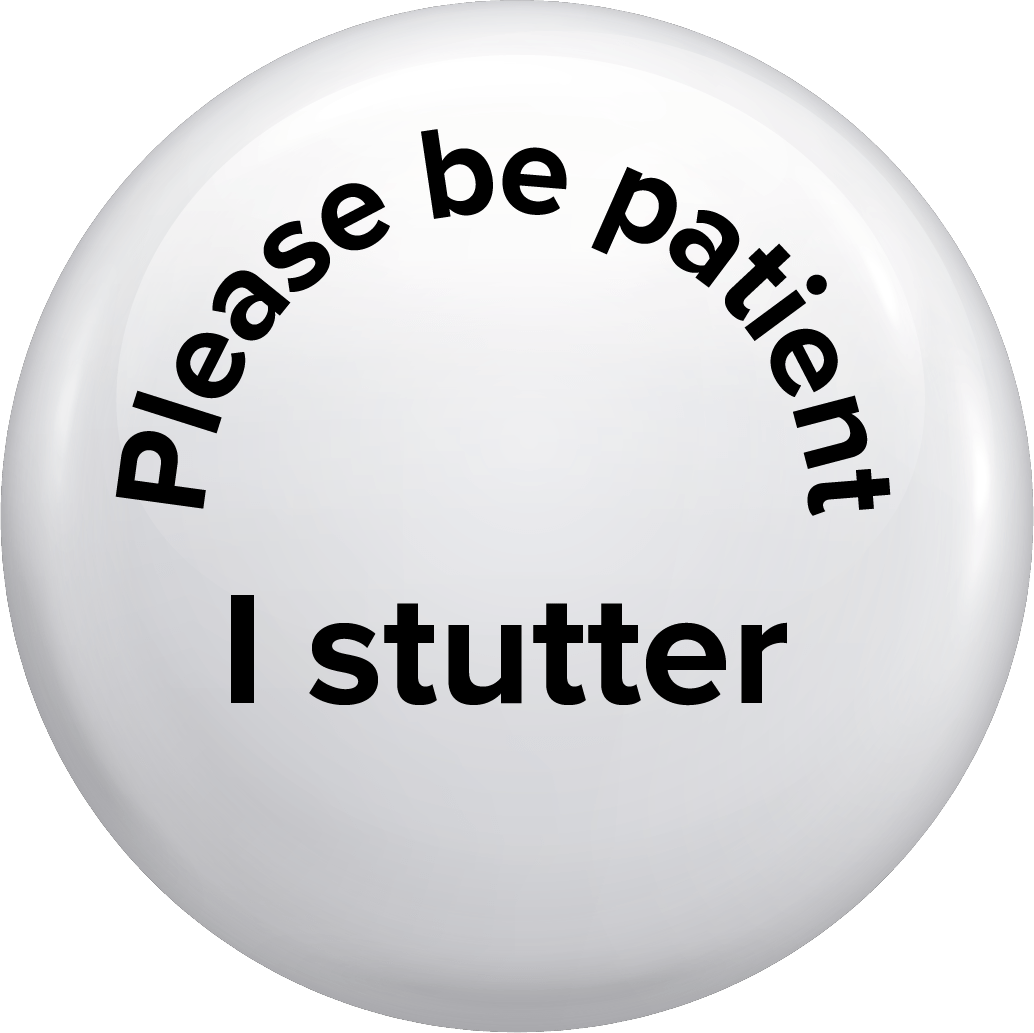

“I recently moved from State College to Seattle, Washington to start a new job,” Krishnakumar said. “Periods of transition always increase the intensity of stuttering for me, so the disruptions caused by my stutter have increased recently. Where I used to try to hide my stutter, I now literally wear it on my sleeve. Every day, I wear a button that reads, ‘Please be patient. I stutter.’

“Patience can really go a long way when communicating with someone who stutters,” Krishnakumar continued. “Resist the urges to finish people’s words, interrupt, or leave a conversation. Actually, my stutter has become a filter of sorts for me. If someone does not have the patience to let me talk, then they are probably not someone I want to invest in, anyhow.”

People at the clinic treated Krishnakumar as a whole person rather than as a problem embedded in a person. This, Krishnakumar said, empowered him to take greater charge of his stutter and his life.

Serving people with hearing issues

In addition to speech and language services, the clinic also serves those who have auditory challenges. The Speech, Language, and Hearing Clinic evaluates hearing, equips and programs hearing aids, and provides auditory processing and rehabilitation therapy. These services are critical for central Pennsylvania because three out of every one thousand children are born with hearing loss, and many more people develop hearing problems over time.

Children who grow up with undiagnosed hearing challenges experience difficulty developing speech, language, and social skills. Meanwhile, older adults with undiagnosed hearing problems face faster rates of brain atrophy and are more likely to be socially withdrawn—even with their spouses.

“I save marriages every day, one hearing aid at a time,” said Leslie Purcell AuD, assistant teaching professor of communication sciences and disorders and audiologist at the clinic. “Communication is an important part of a marriage. If there is a break in that communication, such as with hearing loss, it can lead to lead to greater problems in the relationship.”

Married people, of course, are not the only beneficiaries of the clinic’s audiology services. Clinic staff and students provide hearing screenings and services for students in 12 school districts and four charter schools in the region.

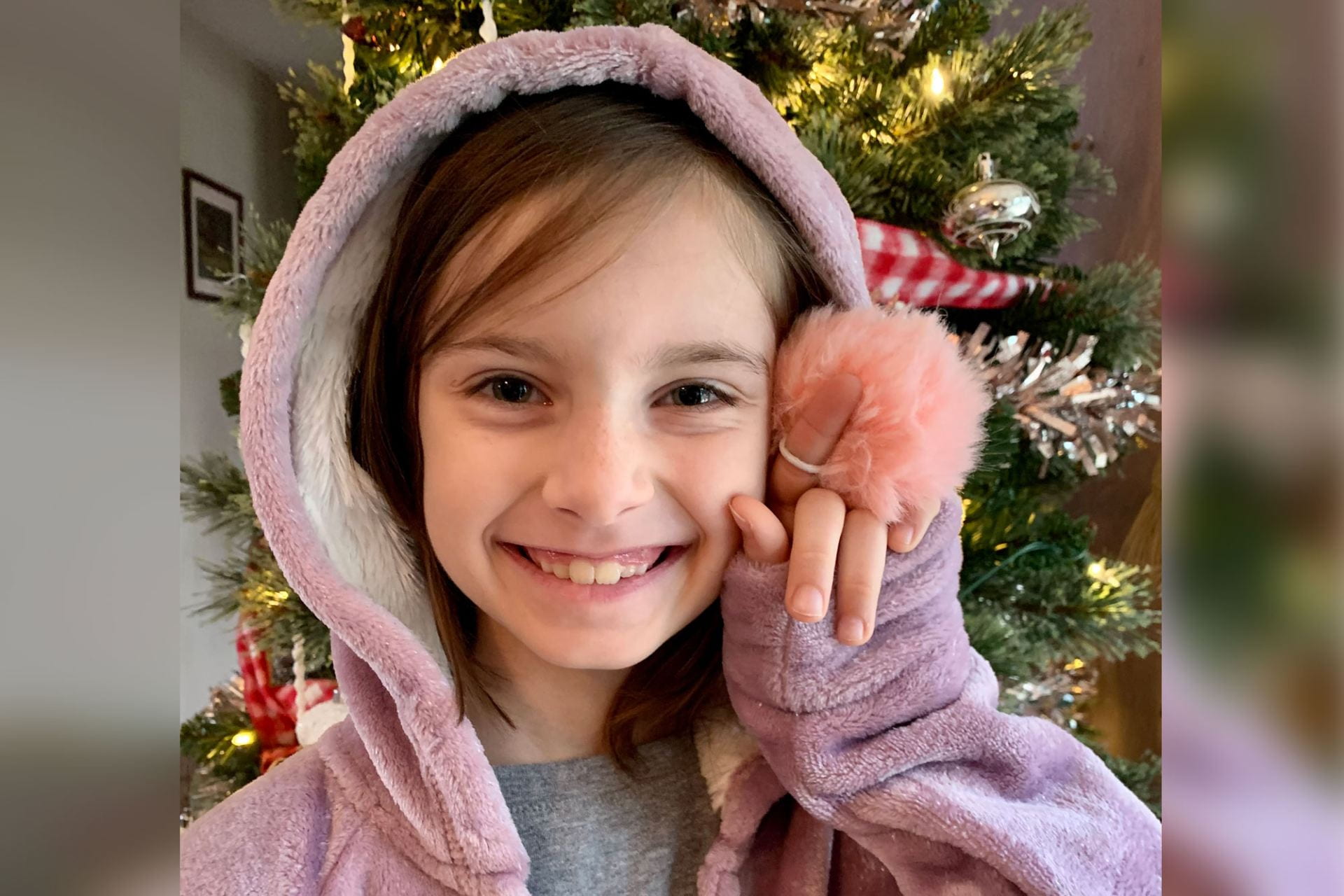

Cilicia is an eight-year-old girl who has been working with the clinic since spring 2022. Cilicia is a social butterfly who loves her friends, but some types of play can be complicated for her. She lives with central auditory processing disorder (CAPD), a condition where people have difficulty engaging with spoken language.

– Leslie Purcell AuD

Assistant Teaching Professor and Audiologist at the clinic

“It can be hard for her when kids want to play a game that has multiple steps or rules,” explained Cilicia’s mother, Diana Spicer. “With CAPD, it can be difficult to quickly process and respond to multi-step instructions.

“Of course, this also creates challenges at home,” Diana continued. “My husband will sometimes say, ‘Please put your listening devices on me,’ meaning Cilicia’s eyes, because she often will not hear or comprehend what we are saying unless she is making eye contact.”

Cilicia works with Megan Mapes AuD, audiologist at the clinic and assistant teaching professor of communication sciences and disorders. Mapes is helping Cilicia learn to tune out background noise and attend to sounds that really matter, like speech directed at the listener.

According to Diana, Cilicia was struggling with how challenging therapy at the clinic is, and the clinic staff adapted the setting to make the process easier and more fun for her. Like Sandeep Krishnakumar, Diana expressed gratitude for the humane and individualized treatment provided by the clinic.

“Most people have not heard of CAPD,“ Diana said. “Until a little more than a year ago, I hadn’t even heard of it. In general, not knowing a condition exists and is causing certain symptoms can affect a person’s sense of self-worth. Now that Cilicia understands her experiences are the result of CAPD — rather than a personal flaw or failure — she can be more patient with herself. This knowledge provides her with the confidence to express her specific needs and better communicate with others.”

When dealing with hearing problems or speech problems, the staff at the Speech, Language, and Hearing Clinic believe it is never sufficient to treat only the condition that brought the person through the door.

“Only by working to understand each person as an individual—their goals, their abilities, their stage of life—can we hope to maximize that person’s communication abilities,” Purcell said. “At the Speech, Language, and Hearing Clinic, we are committed to serving each person and their family in an individualized way to meet their goals.”

Sandeep Krishnakumar learned to embrace the value of his speech and to develop the tools to address and thrive with a stutter. Cilicia Spicer is learning to attend to speech and sounds that matter in order to better navigate her relationships and the world. Every client at the Speech, Language, and Hearing Clinic has a different story because every client is treated as an individual. For many people, the effect of being treated as a whole person affects their entire life.

Photo Credits

Pennsylvania Graphic: by Penn State

Button Graphic: photo by Nikolamirejovska via Getty Images

Sandeep Krishnakumar photo: courtesy of Sandeep Krishnakumar

Slider images of Cilicia Spicer: courtesy of the Spicer family.